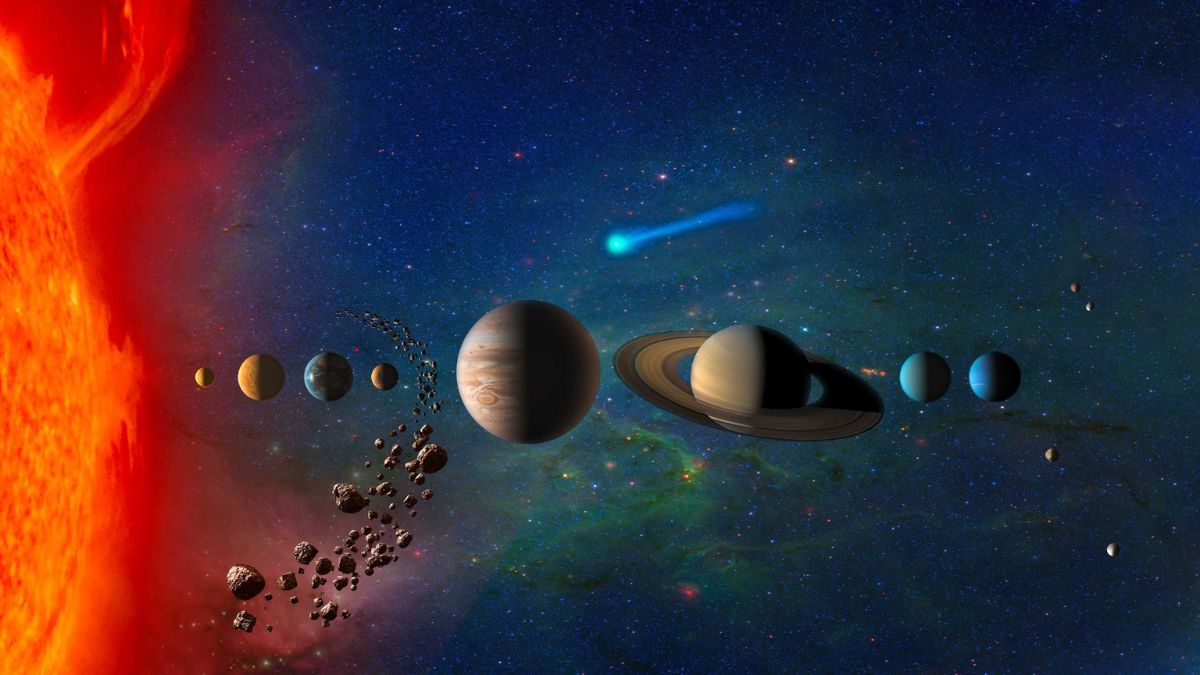

NASA’s latest chase across the solar system has the feel of a cosmic breaking-news alert—an all-hands, all-instruments scramble to catch a ghostly visitor drifting in from the stars. Comet 3I/ATLAS, only the third confirmed interstellar object to swing through our neighborhood, has triggered a rare, coordinated observation campaign across a dozen spacecraft, from Mars orbit to Sun-watching probes.

And while NASA has discovered and cataloged thousands of comets over the decades, this one hits differently. It’s not “ours.” It’s a wanderer from another system entirely—carrying chemical fingerprints that could rewrite what we think we know about how planets and comets form elsewhere.

Table of Contents

Why 3I/ATLAS Has NASA in a Sprint

To astronomers inside NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the discovery on July 1 by the ATLAS telescope in Chile was a moment of calculated excitement. Interstellar objects don’t politely announce themselves; they cut through our solar system fast, bright, and unpredictable. And their composition—untouched by our Sun until now—gives scientists a rare sample of alien chemistry.

NASA quickly mobilized assets scattered across the solar system. The agency’s own summary, available through its official NASA Solar System Exploration portal and condensed via go.nasa.gov/3I-ATLAS, paints the picture of an unprecedented, cross-planet observation network.

For researchers, the question isn’t just what 3I/ATLAS is made of, but what it isn’t. Does it shed particles like our comets? Does it form a tail the same way? Does sunlight alter its chemistry? And maybe the biggest unknown—did it originate from a planetary system that looks anything like ours?

Mars Steps In as the Closest Witness

When 3I/ATLAS drifted past Mars earlier this fall at a distance of roughly 19 million miles, NASA’s fleet at the Red Planet suddenly became front-row observers.

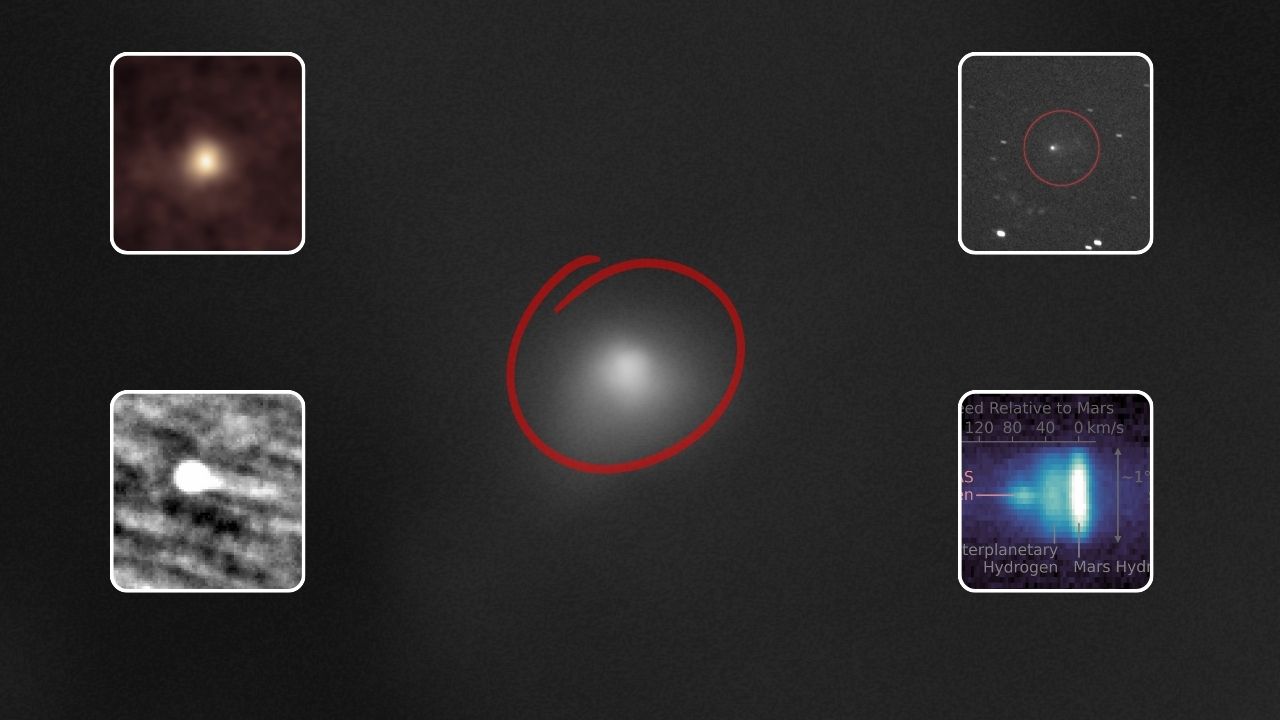

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, with its sharply tuned instruments normally focused on canyon walls and dust storms, snapped some of the closest images we may ever get of an interstellar traveler. Meanwhile, the MAVEN spacecraft—usually busy studying Mars’ atmosphere—turned its ultraviolet eye toward the comet, collecting data that will help scientists decode the gases shedding off its surface.

Even the Perseverance rover, perched inside Jezero Crater, took a faint but meaningful look from the Martian surface. Imagine standing on Mars, pointing a camera upward, and catching a glimpse of an object that didn’t even belong to our Sun. It’s the kind of moment the mission teams quietly savor.

A Sun-Skirting Chase from Heliophysics Missions

Back near Earth, NASA’s Sun-watching fleet took over the job nobody else could handle: watching 3I/ATLAS as it slipped behind the Sun from our perspective.

The STEREO spacecraft tracked the comet for weeks in September and early October. Not long after, SOHO, a joint effort between NASA and the European Space Agency, stepped in to monitor the comet from Oct. 15–26, catching movements invisible from Earth-based telescopes.

And then there’s PUNCH, NASA’s newer mission designed to map the solar corona and solar wind. Its cameras captured the comet’s tail as it drifted through fields of energized particles—an opportunity scientists didn’t take lightly. According to resources published on NASA’s Heliophysics Division site, this marks the first time these missions have purposely tracked an interstellar object.

Even in a field that’s seen Halley’s Comet, sungrazers, and thousands of icy wanderers, this was a first.

We've just released the latest images of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, as observed by eight different spacecraft, satellites, and telescopes.

— NASA (@NASA) November 19, 2025

Here's what we've learned about the comet — and how we're studying it across the solar system: https://t.co/ZIt1Qq6DSp pic.twitter.com/ITD6BqVlGn

Asteroid Explorers Join the Hunt

At the fringes of the inner solar system, two robotic explorers—Psyche and Lucy—were minding their own business on long-haul asteroid missions. But when you’ve got instruments capable of picking up distant objects, you don’t just ignore an interstellar visitor drifting across your lane.

On Sept. 8–9, Psyche captured four observations over an eight-hour window from 33 million miles away. That data may sound remote, but the mission team says it helps tighten estimates of the comet’s trajectory—crucial when you’re dealing with a fast-moving object from deep space.

Lucy, farther out at 240 million miles, did what deep-space imagers do best: stacked a series of faint exposures to reveal the comet’s coma and tail. For an object so distant, those stacked frames are like enhancing a whisper into a full sentence.

A Rare Sky Event Backed by Heavyweight Telescopes

The ground-based ATLAS system that originally discovered 3I/ATLAS operates as part of a NASA-funded early-warning network for asteroids. Once the alert went out, the big observatories lined up.

Hubble took its turn in late July, followed by the James Webb Space Telescope in August. Then came SPHEREx, NASA’s new spectroscopy mission designed to map the entire sky in near-infrared—an ideal tool for distinguishing the chemical signatures in the comet’s icy shell.

These observations aren’t just pretty pictures. Each wavelength tells a different part of the comet’s story: what molecules survive the trip through the solar system, which ones evaporate instantly, and what that means about the temperatures and conditions where the comet originally formed.

The Road Ahead: A Distant Flyby and a Long Goodbye

3I/ATLAS will make its closest pass to Earth on Dec. 19, although “close” is relative—170 million miles, almost twice the Earth-Sun distance. There’s no threat here, no headlines about near-misses. Just a brief, icy hello from an interstellar traveler.

By spring 2026, the comet will cross Jupiter’s orbit and start fading into the dark. The data NASA collects between now and then will help scientists test long-standing theories about how different solar systems build their comets. One interstellar visitor isn’t enough to rewrite textbooks, but each one is a datapoint in a growing puzzle.

And considering we didn’t detect a single interstellar object until 2017, when ‘Oumuamua came streaking in unexpectedly, these visitors may be more common than we thought.

NASA’s statement on the campaign can be found at go.nasa.gov/3I-ATLAS, and observational logs match those published by missions like SOHO, STEREO, and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

FAQs:

How do scientists know 3I/ATLAS is interstellar?

Its orbit is hyperbolic—too fast and too open to be captured by the Sun’s gravity. Only interstellar visitors behave this way.

Can 3I/ATLAS be seen from Earth with a telescope?

It’s extremely faint. Professional observatories can capture it, but it’s not visible to backyard telescopes.

Does this comet pose any danger to Earth?

None at all. Its closest pass is 170 million miles away, nearly twice the Earth-Sun distance.