What once sounded like science fiction is now inching closer to science fact. For the first time ever, scientists have managed to create a laboratory version of a black hole — and guess what? It glowed. This glow is eerily similar to the mysterious radiation that physicist Stephen Hawking predicted nearly 50 years ago: Hawking radiation.

The experiment didn’t involve a giant cosmic monster, but rather a simple chain of atoms. Still, the result could finally help bridge the gap between the biggest ideas in physics — Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. Let’s break it down.

Table of Contents

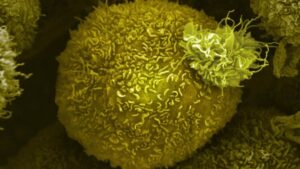

Blackhole

A black hole is one of the most extreme objects in space. It’s formed when a massive star collapses under its own gravity, compressing matter into a tiny, dense core. The result? A region where gravity is so intense that nothing — not even light — can escape. That’s why it’s “black.”

At the edge of this region is the event horizon — the point of no return. Once anything crosses it, there’s no coming back.

But in 1974, Stephen Hawking flipped the entire concept on its head. Using quantum mechanics, he proposed that black holes aren’t totally dark. Instead, they could emit a tiny bit of radiation — now known as Hawking radiation. The problem? It was never directly seen. The signal would be far too weak to detect in space.

Simulation

So, how do you study something that can’t be observed directly? You build a fake one. That’s exactly what a group of scientists from the University of Amsterdam did in 2022.

Using a one-dimensional chain of atoms, they allowed electrons to “hop” from one atom to another. By adjusting how the electrons moved, they created an artificial event horizon. In this simulated space, certain electron properties just… vanished, mimicking the conditions near a real black hole.

And then something incredible happened.

The system started to emit radiation — faint, but there. It behaved just like the thermal energy Hawking described. After nearly five decades of theory, they were finally seeing something real.

Result

The emitted radiation in this setup acted like heat — but only under specific conditions. It wasn’t random. The glow only appeared when a part of the atomic system expanded beyond the artificial event horizon.

This suggests that Hawking radiation might not be a universal effect. It may only occur under certain circumstances, such as when space-time shifts or stretches.

One key takeaway? The simulation points to quantum entanglement playing a role in the radiation’s formation. That’s the spooky, science-y idea where particles remain connected, even when separated by vast distances.

Significance

This experiment matters more than you might think. Real black holes are almost impossible to study directly — they’re too far, too massive, and too dark. But lab-made versions allow scientists to test theories in a controlled environment. No rockets required.

And if this artificial radiation truly mirrors Hawking’s prediction, it could unlock a path to unifying physics. Right now, general relativity (big stuff like planets and gravity) doesn’t play well with quantum mechanics (tiny particles and forces). But black holes sit right at the intersection of the two.

Studying Hawking radiation is like having the missing puzzle piece — a way to finally connect the laws of the large and the small.

Legacy

Stephen Hawking spent his life trying to understand the universe’s deepest secrets. His 1974 theory turned black holes from cosmic dead ends into energetic objects capable of evaporation and, possibly, dying.

Now, thanks to this experiment, we’re one step closer to proving he was right. The glow seen in this atomic chain could be the first “visible” sign of Hawking radiation — even if it’s in a lab and not floating out in space.

It’s a big deal. Not just for Hawking’s legacy, but for the future of physics itself. The more we understand about black holes, the closer we get to unlocking the code of the universe.

FAQs

What is Hawking radiation?

A weak energy black holes may emit, predicted by Stephen Hawking.

Was it seen in a real black hole?

No, it was seen in a lab-made black hole simulation.

How was the black hole simulated?

Using a chain of atoms and controlled electron movement.

Why is this discovery important?

It supports Hawking’s theory and helps link physics laws.

Who conducted the experiment?

A team from the University of Amsterdam in 2022.