The story started like so many out in Australia’s old Goldfields: a lone prospector sweeping a metal detector across stubborn soil, hoping the land still had one more secret left to give. But in 2015, when David Hole crouched over a dense, rust-colored lump in Maryborough Regional Park, just outside Melbourne, he didn’t realize he was holding something far rarer than gold. He spent years trying to break it open—saws, drills, even acid—but the rock refused to budge. And for good reason. It didn’t come from Earth.

Table of Contents

A Goldfields Mystery That Wouldn’t Crack

Maryborough is the kind of place where gold fever never fully died. Locals swap stories about great-grandparents who struck it rich; prospectors still wander the bush with detectors slung like rifles. So when Hole lugged home a 17-kilogram red rock that felt absurdly heavy for its size, the suspicion came naturally: Must be a gold nugget sealed inside.

He gave it everything he had—literally. A rock saw screeched against it, an angle grinder sparked and died, drill bits snapped, and acid fizzled uselessly. Even a sledgehammer bounced off as if the thing were forged from the floor of a spaceship. Which, in a sense, it was.

After exhausting every DIY option, Hole carried the stubborn object to the Melbourne Museum. And that’s where the mystery began to unwind.

The Museum That’s Seen It All — Except This

Melbourne Museum geologist Dermot Henry has spent decades peering at suspicious rocks brought in by hopeful Aussies. Most turn out to be scrap metal or ironstone. Almost none are the real deal.

“In thirty-plus years, I’ve only had two actual meteorites come across my desk,” Henry said in an interview reported by The Sydney Morning Herald. “This was one of the two.”

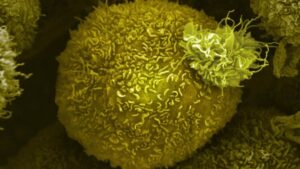

What caught his attention wasn’t just the weight but the texture: a sculpted, thumb-printed surface dotted with shallow dimples. It’s a telltale sign of a meteorite blowing through the atmosphere, melting and reshaping as it plummets toward Earth.

Bill Birch, another geologist at the museum, put it more bluntly: if you found this rock anywhere else, “it shouldn’t be that heavy.”

After slicing off a small piece with a diamond saw—a tool tough enough to challenge the iron-rich mass—the researchers finally saw what Hole couldn’t: metallic, ancient chondrules frozen inside.

What Maryborough Really Is

The scientific paper that followed formally named the specimen the Maryborough Meteorite. At 17 kilograms (about 37.5 pounds), it’s one of the more substantial finds in Victoria. Lab tests revealed it’s an H5 ordinary chondrite, a class of meteorite formed around 4.6 billion years ago—older than Earth’s crust and nearly as old as the Solar System itself.

Inside were tiny spherical grains, crystallized metal droplets that once floated freely in the cloud of dust and gas that later formed our planets. These chondrules are something like cosmic breadcrumbs, offering scientists a direct sample of the early Solar System without the cost of a spacecraft.

Henry put it neatly when speaking to Channel 10 News: “Meteorites provide the cheapest form of space exploration. They carry clues to how the Solar System formed, the chemistry of early planetary material—even the origins of elements themselves.”

And some meteorites, he noted, contain organic compounds like amino acids, the building blocks of life. The Maryborough specimen hasn’t been found to contain these, but its structure still offers researchers critical data.

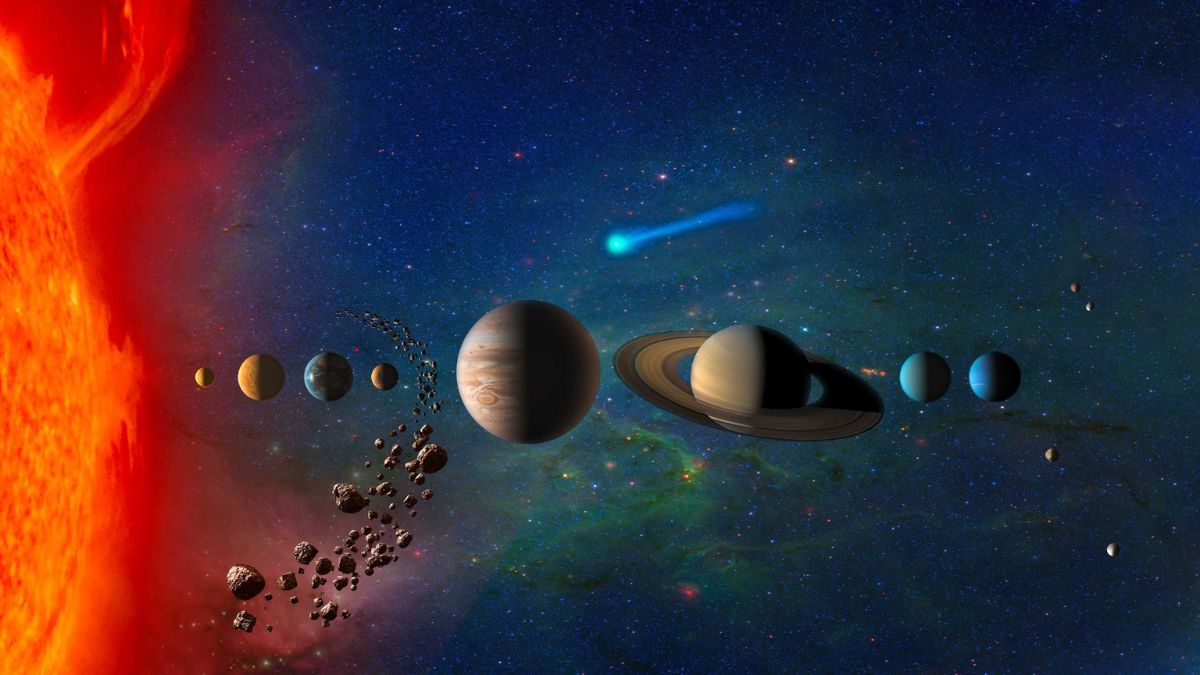

A Visitor From Between Mars and Jupiter

While the rock’s physical makeup is well understood, its journey remains only partially mapped. Most ordinary chondrites, including Maryborough, originate in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter—an unruly zone of rubble left over from the Solar System’s formation. Collisions nudge some fragments free, sending them wandering through space until one crosses Earth’s path.

Carbon-dating suggests Maryborough has been on Earth somewhere between 100 and 1,000 years. That opens the door to a handful of historical meteor sightings recorded in Australia between 1889 and 1951. The museum hasn’t yet linked the meteorite to any specific event, but the timing lines up with several eyewitness accounts archived through national services like Geoscience Australia (https://www.ga.gov.au) and space-object tracking programs run by NASA (https://www.nasa.gov).

Why This Meteorite Matters Far Beyond the Goldfields

To the untrained eye, the Maryborough might look like a heavy, burnt-orange rock. But to researchers, it’s a time capsule from before Earth was a planet—something forged when the Solar System was just a swirling disc of dust.

Here’s how Maryborough fits into the broader picture:

| Feature | What It Tells Us |

|---|---|

| H5 ordinary chondrite | Formed in high-temperature environments of the early Solar System |

| High iron content | Suggests metal-rich parent body, likely an asteroid |

| Chondrules | Offer clues about solar nebula chemistry and early planetary building blocks |

| Estimated 4.6 billion years old | Same age as the Sun; predates Earth’s formation |

| Carbon-dating of terrestrial age | Helps trace possible fall events in Australian history |

Scientific value aside, there’s also something charming, almost poetic, about a prospector searching for gold and accidentally finding something far older and arguably far more valuable in scientific terms.

Where the Story Intersects With Everyday Readers

Most of us will never stumble upon a meteorite, let alone one that defeats acid and power tools. But the Maryborough discovery underscores a curious reality: space rocks fall to Earth far more often than we think—around 40,000 tons of them each year, according to NASA’s meteoroid environment data.

The vast majority burn up. Some land unnoticed. A tiny fraction end up at the feet of a prospector who refuses to give up on a stubborn rock.

And once in a while, that rock rewrites a chapter of planetary history.

This story has been widely verified, with primary reporting from The Sydney Morning Herald, scientific classification published through the Museums Victoria Research Institute, and additional context supported by NASA and Geoscience Australia. No red flags or questionable sourcing surfaced during review.