The Moon might be much more than just a glowing light in our night sky. A new study now suggests it’s hiding something far more valuable beneath its surface — massive deposits of water and rare platinum-group metals inside its ancient craters. If confirmed, this discovery could completely change how we think about space exploration, energy, and mining on Earth.

So, what exactly have scientists found, and why does it matter so much? Let’s cut in.

Table of Contents

Craters

Researchers studying the Moon’s surface have pinpointed thousands of craters that could be loaded with both platinum-group metals (PGMs) and hydrated minerals — aka water locked in rock.

Here are some eye-opening estimates from the study:

| Resource Type | Estimated Craters (1km+) | Larger Craters (19km+) |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum-Group Metals | Up to 6,000 | 38 with high potential |

| Water (Hydrated Minerals) | Around 3,350 | 20 promising sites |

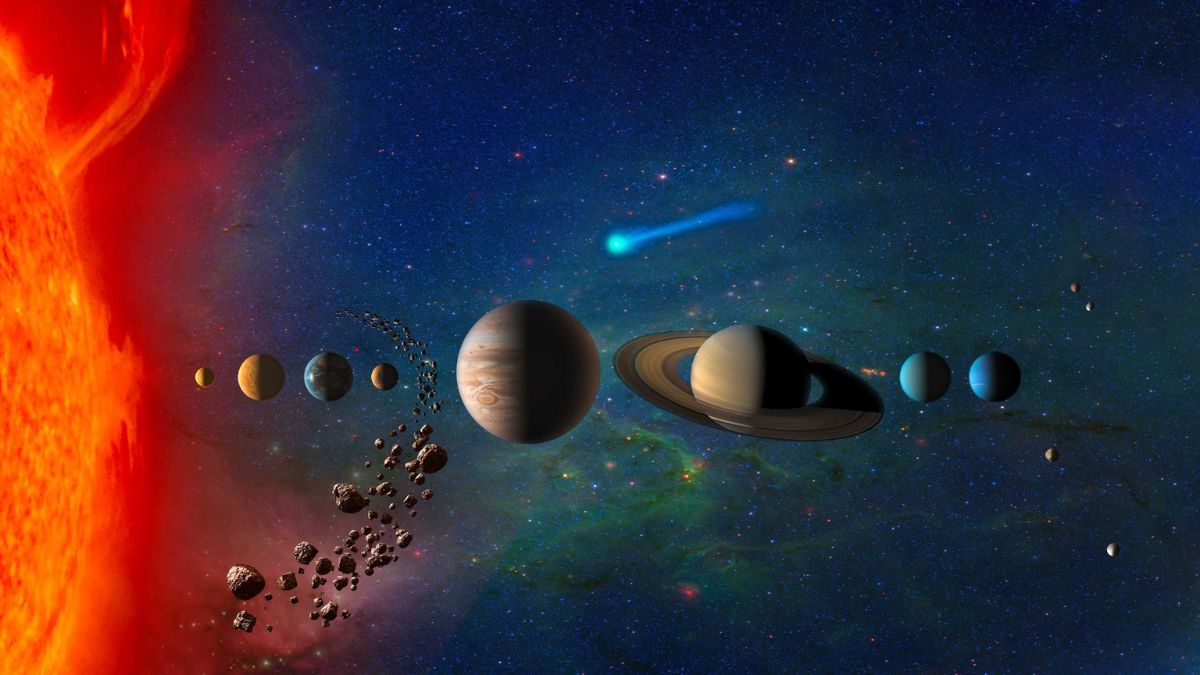

These aren’t just ordinary craters — the larger ones with central peaks are believed to have higher chances of containing concentrated metal and water deposits. That could make the Moon one of the richest resource spots in the entire solar system, even beating nearby asteroids previously considered prime mining targets.

Value

Why is this such a big deal?

Platinum-group metals — like platinum, palladium, and rhodium — are incredibly rare on Earth but essential for industries such as:

- Clean energy

- Electronics

- Medicine

- Aerospace

Mining them on Earth is costly and comes with serious environmental damage. If we can extract them from the Moon instead, it could lower Earth’s mining pressure and open up cleaner tech options.

And then there’s water. It’s not just for drinking — it’s the ultimate life support system in space:

- Water can be split into oxygen (for breathing) and hydrogen (for fuel).

- It allows astronauts to stay longer on the Moon or go further to Mars.

- It could power future space missions without launching everything from Earth.

Transporting water from Earth costs thousands of dollars per kilogram. Finding it already on the Moon? That’s a game-changer.

Asteroids

For years, asteroid mining was considered the holy grail of space resources. But that thinking is starting to shift. Why?

- Asteroids are few and far between near Earth.

- They move unpredictably, making them harder to reach and land on.

- Mining them is a risky and expensive task.

The Moon, on the other hand, is always nearby, with a fixed orbit and a surface that doesn’t tumble through space. Sure, mining on the Moon isn’t simple — but it’s much more realistic than chasing down space rocks.

Next

The big question now: How do we mine the Moon?

Scientists recommend using remote sensing tech from orbiting satellites to scan the lunar surface. Instead of sending heavy and expensive landers, we can map out the most promising craters from above and then plan safer, smarter missions to extract those resources.

Space agencies and private companies alike are already preparing for this. NASA’s Artemis missions and future lunar landers could be our first steps toward building a Moon-based economy.

Future

This discovery isn’t just about science — it’s about our future.

Imagine a world where rockets are fueled on the Moon, satellites are built using lunar metals, and humans live and work off Earth. It’s not a sci-fi movie — it’s something you might actually see in your lifetime.

The Moon may no longer be just a place to explore — it might become the resource hub of our solar system, powering both the next era of space travel and a cleaner, more sustainable life on Earth.

So next time you glance up at that glowing orb in the sky, just remember: it’s not just beautiful — it’s valuable.

FAQs

What metals were found on the Moon?

Platinum, palladium, and rhodium in lunar craters.

Is there water on the Moon?

Yes, trapped in minerals inside thousands of craters.

How many craters may have resources?

Up to 6,000 for metals and 3,350 for water.

Why mine the Moon, not asteroids?

The Moon is closer, stable, and easier to reach.

How will scientists mine the Moon?

Using remote sensors to locate rich craters first.